The Perils of Name Changes … and Alternatives.

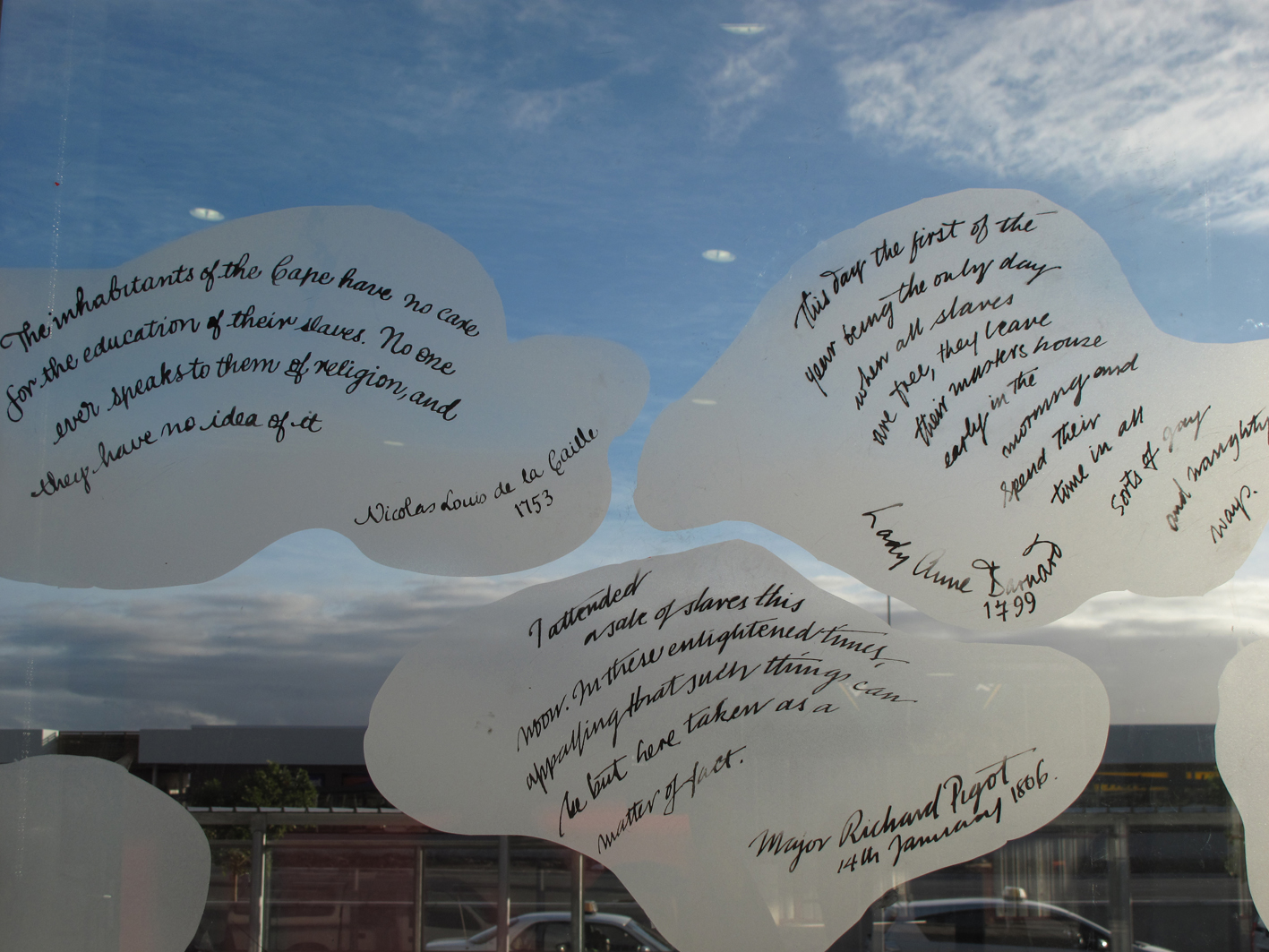

A Random History - public art work by Sue Williamson on the My Citi Bus Station at the airport. Photo courtesy of the artist

In this piece I discuss contestations around identity.

These are complex political times. I want to look at recent events in Cape Town around a process to change the name of the city's airport. I suggest that we can see this moment as an opportunity to reflect on alternatives for addressing deep underlying currents.

A Naming Process Begins

At the end of May 2018, the Airports Company South Africa (ACSA) gave just one week’s notice for a public participation process to rename Cape Town International Airport. This followed an emotive call and petition by populist political party the EFF to re-name the airport after the much maligned and recently deceased struggle hero Winnie Madikizela-Mandela. The national transport minister issued instructions to re-name four airports, putting forward names of three celebrated black political leaders from the ANC and one from the PAC (Robert Sobukwe). The naming project is part of the Department of Arts and Culture's (DAC) ‘Transformation of the Heritage Landscape’ programme. Launched in 2016, this programme aims to remove ‘offensive names’ and deal with a variety of other issues too - including reintroducing a school history curriculumthat speaks to the liberation struggle. As is often the case in ‘new’ post-colonial societies such programmes are highly politicised exercises. They are often used, as in this case, to valorize certain power interests.

This is not a good time in this city for such rash emotive projects. Cape Town has been wracked with complex socio-political issues, all of which have explicit racialised elements ranging from a crisis surrounding the Mayoral position and various protests and struggles. Predictably the public participation meeting held at the airport to discuss the name change turned ugly with racism and intolerance rearing its twin heads. The debates have continued on Facebook where angry, bigoted responses continued alongside more moderate views. As commentator Judith February rightly says: "The problem is that one needs to ask a primary question: why are we suggesting a name change for Cape Town International in the first place?......All that the renaming ‘debate’ is doing is fuelling unnecessary tensions in a country and a city that can frankly do without this squabbling." She asks whether it would not be better"to find ways of public education which are instructive and which help us all to link the past to the present in ways which are deeply meaningful. Connecting these dots is crucial for true transformation and inclusivity in our cities and towns."

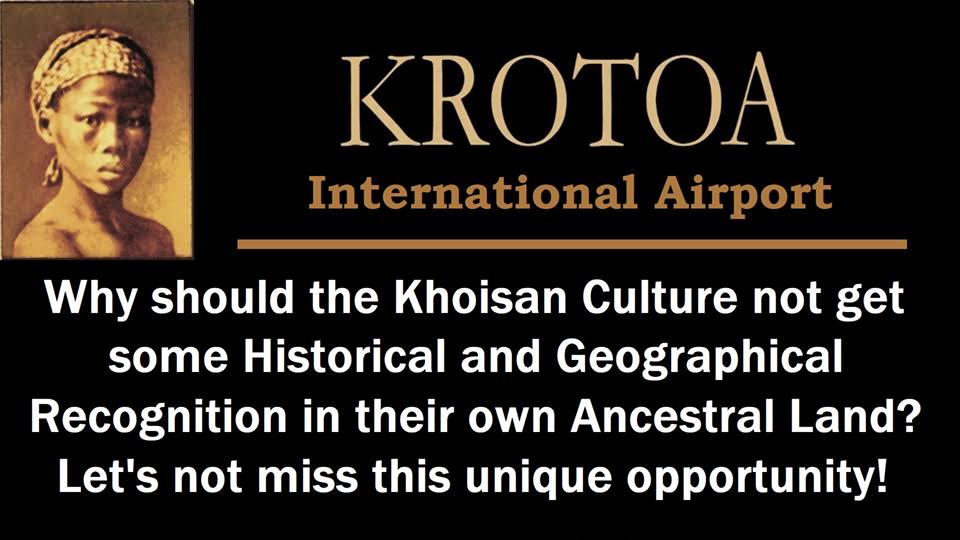

A meme currently doing the rounds on social media calling for the airport to be named after a Khoi woman who has a history with the arrival of the Dutch - Krotoa

This is a message that this blog has also put forward previously. February outlines some of these tensions, but I'd like to consider these with some additions and other recent developments adding to earlier writing on Cape Town's complex histories, on race, culture and power and on symbolic reparations.

A People Marginalised

Firstly, people of colour are feeling increasingly marginalised in Cape Town - socially, culturally and economically. Rising fuel, water, electricity and VAT costs have added burdens to the already stressed lives of the poor. This is not helped by the national ‘crisis of corruption’ which has led to, amongst other things, a collapsing rail system - adding additional financial burdens. The region and city's centrist government has played its own role by giving significant concessions to developers, feeding a cycle of gentrification and displacement, while at the same time shipping evictees, homeless people and the poor to inadequate habitats on the edge of the city. There have been recent high-profile protests against developments on the edges of the historic ‘Cape Malay’ neighbourhood of Bo Kaap – part of ongoing struggles for inclusionary housing in the city. It can also be seen in the closure of historical springs, as a result of complaints by moneyed residents, in a city where tangible heritage is normally dealt with through more rigorous processes. Thus the party controlling the region is seen as a vehicle of white privilege, seemingly unwilling to acknowledge this key aspect of its identity and is increasingly viewed with suspicion.

Secondly, people of colour have long complained about their continuing invisibility in various parts of the city and more especially in respect to finding work or moving up the ladder. A young black woman's letter to Cape Town as she leaves for opportunities in Johannesburg was shared extensively on social media and appeared as a front-page story in the press. It is indicative of the experiences many people of colour have.

Thirdly, mixed race (or so called "coloured") people in the city have been going through a crisis of identity for some time. This is a complex issue with many levels. It has been exacerbated by the term ‘Coloured’ being continued as a marker in post-apartheid society. As a result there are a number of people who see themselves as a distinct race or culture, although there are vast differences between people placed in the category that have to do with class, family biographies, region and the like. Thus Gasant Abader, the editor of a daily newspaper can call on the complexity of his identity but still fall into the trap of essentializing ‘colouredness’ - drawing on distinctly Cape Town traditions that would not sit as well with people labelled similarly from Durban or Johannesburg for example: "I am proud of my coloured identity. I jol with the klopse, eat gatsbys, speak in a special dialect when I’m with my own, and participate in many other practices that are unmistakably coloured."

But what has emerged in this region for a sizeable group of people, is a self-identification with indigeneity - identifying oneself as Khoi or San descent. For many this appears to be a way to claim being of the land and challenge the view that South Africa is a country of black Nguni descent people. This is a vocally militant group, a section of which disrupted the airport public participation meeting. A much smaller group connect their stories to Cape Town's complex slave histories.

pic by David Harrison (M&G) from an excellent article by Sean Jacobs and Zachary Levenson on The Limits of Coloured Nationalism

Fourthly, working class "coloureds", more especially, are feeling threatened by a growing black population in the city. For many decades, colonists and later the Apartheid government, made it difficult for black people to be in Cape Town. Then from the ‘80s this changed following an influx of largely rural Xhosa people from the Eastern Cape which has continued into the current day. From 2011 - 2016, for example Cape Town swelled by around 350 000 migrants, the largest proportion ofthese being young job seekers from the Eastern Cape, a province bedevilled by corruption and mismanagement. This is creating tensions around housing and jobs in the Western Cape. Furthermore the migrants are a traditional ANC constituency who have been militantly vocal, sometimes through the party, about rights to houses and services. As a result, the threatened group see the migration as politically organised - as a way to ‘own’ Cape Town. This has resulted in a rise of racism and intolerance by some groupings of coloured people against blacks generally, which flared into violence recently in Parklands and led to the emergence of a right-wing groupings ‘Gatvol Capetonian’. This is a reactionary nationalism suggest Jacobs and Levenson pointing out the limits of such thinking.

The challenging issues around race are aggravated by various national events - high profile cases of racism by white people against people of color, comments by minority interest groups that deny the violence of Apartheid, as well as a recent high profile racist incident by the EFF against a person of Indian descent during a parliamentary hearing.

Why see this as an opportunity?

The issue of race is one South Africa has barely dealt with. Bar the DAC's insipid Social Cohesion program, on which one is hard pressed to find any information, there is no program at any level seeking to address a national agenda of tolerance, and none that seek to deal with non-racialism. In a country that has been shaped and ordered by race laws and the violence that came with it, this is a shocker of epic proportions. So far transformation has been dealt with through heritage projects.

Symbolism is important - it’s a way to signal change. The name change appears as a quick way to make a grand statement about representation and change. However the timing and process is problematic coming when national, regional and local government actions/inactions and related party dynamics, have created an untenable socio--economic context. Thus, the name change process adds fuel to a fire of racial tensions which has been simmering since the first democratic elections. I have tried to show some of these tensions above and the very real and growing violent responses around them. This may only get worse over the next few months leading up to the elections as politicians turn up the screws in an attempt to win points

Two stencils by the Toklos Collective

If one wanted to start dealing with race though, Cape Town offers a unique opportunity. This is because the city's racialised history de-centralises much of the narrative from up north, which is comfortably black/white, urban/rural. This makes Cape Town a useful laboratory for raising and dealing with questions about non racialism. Instead of seeing the region as a problem, it would do well for the country to see it as a way to make sense of what a new South Africa could look like.

But to make this happen I want to suggest we need to find alternatives to how we are dealing with race. The problematic process of the airport name change begs us to ask the question what these could be. I want to suggest two ways.

The Alternative to Name Changing

The first possibility has implications for local government. It would recognise the role of culture departments as possible vehicles to mediate dialogues, together with civil society partners and thus help societies in the city to reshape the debate around race and non-racialism. This is not the same kind of work that departments dealing with community consultation and public participation do. Moreover its a long term project. There are prerequisites for this to happen. The first is that local government needs to make spaces available for such dialogues, which need to be consistently held over a long period. Initially existing spaces such as Libraries and Community Halls can be used, ideally cultural centres are needed in the longer term. The second is that those working in such contexts need to have conflict resolution, good listening and facilitation skills, as well as in depth knowledge on diversity issues. As cities become increasingly diverse such skills and knowledge is critical. London was especially good at managing diversity programs through its culture departments for many years because of the high levels of ‘difference’ in the city. Because South Africa has flattened its ‘differences’ to 4 main groups, and effectively ignores its large new sub-saharan African migrant community, it does not recognise how complex its diversity is.

The second has implications at a national level - for government, civil society, the media, academia and the religious communities - it is a call for a national debate about the countries continued use of Apartheid racial categorisation. It’s one I believe activists and commentators should making more often and more loudly. For years South Africa has continued to use old Apartheid categories while simultaneously, somehow, hoping for a non-racial future to happen. This appears increasingly unlikely. I suggest, instead of task groups called by ministers, that an ongoing dialogue are held with civil society around racial categorisation and its alternative. By sharing knowledge on multiple platforms and asking for solutions, we can as a nation begin in a more structured way to find some solutions for what is no longer working. It cannot be about absolving the past nor ignoring privilege. We need to confront race and the classification system and discuss what belonging, nationhood, respect mean, how we can acknowledge the past and build a future. It’s not going to be easy and a lot of preparatory work is needed. Of course there will be those who will try to use it for political ends, but we cannot hide away from the fact that race matters in South Africa - it shaped us and continues to do so. And it cannot be driven by the state alone - though the state must resource it. Rather this than limiting short term, politically motivated processes to change names.

Article written by Zayd Minty. Edited by Graham Falken.