The Community Arts Centre as a Fireplace

Indigenous people around a campfire. uncredited photo on the internet

In this piece, a speech given at the shukuma mzansi community arts centres conference (4-6 April 2018), I make an argument to understand community arts/cultural centRes as a "fireplace". I suggest that once we recognise the importance of this convivial sharing space in the lives of our ancestors, we can understand better the basic elements humans need from cultural spaces. This has policy implications. How could it help us shift our mindsets, our ethics and more importantly our practise in responding to the challenges of local context through mobilising culture?

We live in a world where there are significant social, economic, and environmental challenges. Its for this reason, most nations have adopted the 17 Sustainable Development Goals: an attempt to rally humans around a shared cause, in the face of an unprecedented set of connected challenges. Importantly these sustainable goals are not simply "green" issues (water, waste, energy, climate change, our relationship to the natural environment and other living creatures, responsible consumption and production) but also related to "brown" issues (inequality, poverty, basic needs, well being, access to education), and is deeply connected to fostering peaceful coexistence, our ability to accommodate diversity and to ensure gender equity.

The role of culture has become critical in this debate since culture is deeply connected to issues of our identity, our histories and our heritage, how we relate to and how we behave with each other as humans. An understanding of what it means to be human is key. Our challenge of achieving a sustainable planet is a human one, a behavioral issue and thus intricately connected to culture.

Greenpeace Philippines' Dead Whale installation: an artwork raining awareness of waste in oceans.

To address our sustainability challenge, it is recognized, we must think globally and act locally. It means we have to find ways to work at the local level with other humans, meeting their key needs, working with their hopes and fears, ensuring their well being and bringing to consciousness the implications of everyday actions in its broader context. How we deal with waste, with our scarce potable water resources or how we address poverty or violence against others are all intricately connected to our locality, where we feel the impacts most strongly. But these also have repercussions for our city, our country, our continents and ultimately our planet.

A number of key bodies dealing with culture, including Unesco and others have all begun to work with the notion of culture as key to sustainable development, and more especially its local implications. Its for these reasons UCLG asks us to look at Culture as the Fourth Pillar of Sustainability.

The role of Community Arts CENTRES

To think locally means to consider the basic building block of cities, neighborhoods and the communities who live in them. A key issue within these is how the public is able to engage with each other, to talk, to renew itself, to learn, to share, to inspire. Its for these reasons public space is so highly valued for cities - these are where chance encounters happen, where people can be the social being they are, where democracy can be practised. But whether we are talking about open spaces such as parks, or community facilities such as halls, bringing people together in space is not enough, their exchange needs to be activated, and this is why special spaces for engaging with culture are necessary.

Humans have always had spaces of gathering, sharing, learning and inspiring. For most our existence as a species and more especially before the agricultural revolution 12 000 years ago, that space was the fireplace. Homo Sapiens achieved cognition some 70 000 years ago, setting us apart, seemingly, in a significant ways from other animals. Cognition allowed us to far surpass stronger animals, because it gave us the ability to transmit, through sentences, complex knowledge. Through being able to gossip it enabled us to anticipate and ultimately to imagine. Cognition gave us the ability to create myths or "imagine realities" which Harari (2011) suggests has been the reason we as a species have been able to organize at scale, to innovate and to invent in a myriad of ways. While we hunted and gathered, for over 80% of our existence as a species, our main form of communication and social bonding has been around fireplaces, where we spoke, told stories, danced, made music and sometimes painted or made and decorated implements. Thus creative expression is an innate part of us as humans, setting us apart from others and holding us together. Even as we developed more complex arrangements, eventually inventing writing, money, farming and complex settlements including cities, we always needed these social spaces where we transmitted knowledge and values. It is a response in other words to a very basic human need.

Sibikwa Arts Centre in Benoni - rehearsals for a play. uncredited photo on the internet

As a fireplace

I suggest that if we understand Community Arts Centres (CACs) as our modern fireplaces at a local level, we can recognise our human need to gather in safe and convivial arrangements to collectively share and learn. Understanding CACs as such requires us to build on the core needs of our constituency: to be social, to belong, to be safe. Thus we need nurturing spaces that make people want to linger and to return, that offers them meaning. One of the key challenges of an increasingly complex contemporary world is the potential to become disconnected from each other, to loose direction and sense of self. Without owning our identity as humans, individually and in groups, we slip into depression, anxiety and fear and this feeds all forms of social traumas. Owning and valuing our personal and collective identity helps us be better people. CACs can play a significant part in acts of positive togetherness drawing on the innate human need for creative expression. They are not just about the buildings, but about the people who congregate in it, though the need for fixed consistent welcoming spaces vital. These are space that make us want to be in, to contribute to. Such conditions enable to share experiences, help us build on our communities histories, dreams and values, often through creative means. This may seem self evident, but it is easy to forget.

I would argue that in todays age, the demands of keeping centers and projects afloat - fundraising, paying the bills, providing courses, putting on productions, managing buildings in complex conditions, sometimes mean we forget basic needs of fostering inclusive togetherness. In South Africa there is great demand for CAC's to function with very little consistent funding and as a whole the cultural and arts sector is in a precarious position. The demands around working as "creative industries", for cultural workers to be financially self sustainable doesn’t help either. It takes away from the recognition that engaging with our culture at a community level is a human right and as such demands consistent public support.

The Community Arts Project in Cape Town. Photo taken in 2000

How did we get here?

The Bonteheuwel Multipurpose centre in 2000

CACs in South Africa have their beginnings in the 60s, as social movements for change emerged, at the same time other countries around the globe were introducing centers as ways for its citizens to express their creativity and build social cohesion. There was a shift also in recognising the importance of the everyday creativity of the ordinary person and not just the genius artist, and simultaneously a shift from the high arts to the popular as the mediums of distribution changed. In South Africa arts centers were initially driven by liberal whites or missionary for the benefit of black people who were being deprived of an arts opportunities. By the 70s, the rise of black consciousness saw many new centers driven by black creatives who were concerned with empowering their own. The influence of the Gaberone Conference in Botswana in 1982 introduced new ideas of using culture for political change often drawing, for example, on theatre for development, and on silkscreen and lino printing. There was extensive foreign funding for the arts for resistance in South Africa during this period when apartheid repression was at its height. After political change, In the late 90s, government started a community arts center programme and invested R50m in building 41 new arts centers, however no funding was offered to the historic centers who were already facing challenges as overseas funding slowly dried up. Many of the latter centers would eventually collapse. This was a travesty and lost significant momentum to furthering governments social cohesion ambitions.

Governments CAC program ended up being a failure. Many new centers were dysfunctional or closed down by mid 2000. There were a multitude of reasons for this - government had prioritized the hardware (buildings) and not the software (management and programs) and other levels of government, provinces and local, which were meant to come on board into the longer term did not do so, for a multitude of reasons. It would be some time before the research confirmed the reasons. Although national government put in additional support later to establish a national federation of community arts centers, the funding eventually fizzled out, with many regions of the network collapsing. The Flanders and later other EU supporters came on board and managed to provide capacity building and vital exchanges, and some centers were fortunate beneficiaries. One of the biggest challenge has been getting local government on board with consistent funding and enabling frameworks and for provinces to also play a part. Gauteng alone supported to a limited level a network - GOMACC. More recently, after almost a decade of inaction, a small fund was made available, which has ensured a modicum of support and attempted to revive networks in various provinces. However many centers have collapsed by now, and the fund supports a number of projects with ridiculously small amounts of money as well as some capacity building. In a context with so little support, even the little matters. But is this good enough?

The Dramatic Need Piet Patsa Community Arts Centre in the Free State. uncredited photo from the internet

How we do get out ?

The answers for the dilemma are quite clear. These were articulated in the 2004 publication, Inheriting the Flame - published at the time the National Federation was set up with support from the Department of Arts and Culture. In it Joseph Gaylard proposed a three pronged approach drawing on the experience of Flanders. These are predicated on clear cultural policies that are "facilitative" and integrative of community arts and culture centers into local government. What is essential he summarized is: 1. Money: consistent ongoing funding, particularly support from local government for operations, allowing centers sufficient capability to attract further financing for productions and education (two key responsibilities of CACs). This recognises that such centres are public good and cannot be expected to be self sustaining completely. 2. Capacity building- providing a range of "training and technical support to stakeholders at the local level to realize the policy". And 3. Buy-in with "wide consultation and effective communication ensuring stakeholders at a local level both understand and support" the policy. Gerhard Hagg, additionally, identified the following two areas of "buy in": a) addressing local governments concern that there is constitutional hurdle preventing it from providing for culture and b) fostering a more formal co-operative intergovernmental approach where each of the three levels of government are clear about their respective roles.

Sibikwa Arts Centre

Sadly, when one looks at the facts, while there have been some positive changes, on the whole there has been little of significance or at scale since 2004. There are really no two ways about it - for community arts and cultural centers to function and play the kind of role everyone believes is necessary and possible, where they make a difference at the level of local communities including sustainability, then Money, Capacity and Buy in are key. After more than two decades, since community arts centers were first touted at a national policy level, as way to foster cultural democracy, the failure boils down to government needing to do its job better.

But is there a role for the existing cultural centers?

Being more needs based

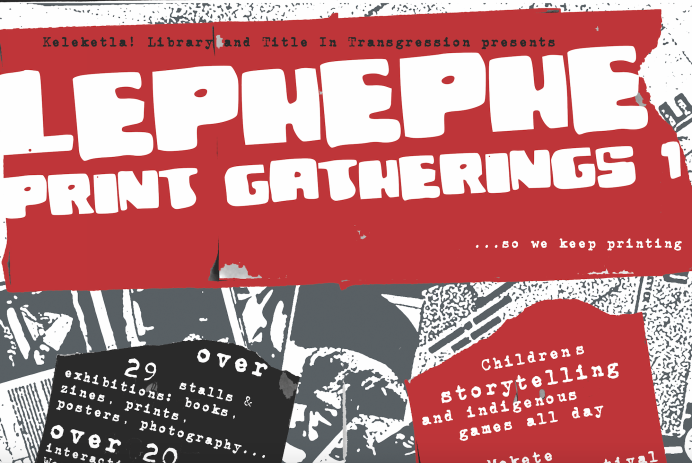

Returning back to the notion of CAC as a fireplace, I would also like to suggest that there are many community arts centres who have not fully grasped the implications of being a place of togetherness, of being spaces were difference is welcomed and a good environment is created for the broader community to engage in, share, learn and be inspired. Too many of those fortunate enough to get support are not leveraging their resources to the maximum. However there are notable others who receive little support, are not formally in the funding stream who show the way by building relevant structures addressing the needs of their communities. We can learn a great deal from the work of bodies like The Keleketla Media Arts Project, Jeppe Photo Club and Trackside Creatives in Johannesburg. The former (pictured below) has worked in especially complex conditions, providing educational programmes for young people and sophisticated noteworthy artistic programmes, often in the absence of government grants, driven by motivated and committed leadership with clear values and direction. We need to learn from such experiences of empowerment more, but more importantly we need to support these successful cases.

At the same time we need to question the format of what a CAC may be, in a time of technological change and in the face of sustainability challenges. Its time to consider how to think about such spaces in new ways, to incorporate the learnings of Makers Spaces (providing basic tools to enable participants to experiment in a collaborative environment) and creative hubs (providing collaborative spaces for collectives, micro businesses and freelancers). We need to learn how to work productively and cleverly with waste, to create new materials. We need to understand how to engage with new technology and a changed media scape. Even in poverty ridden areas in Africa, young people are ensuring they have at least an entry level smart phone, thus placing into their hands a powerful tool for content creation (often needing access only to free wifi). Instead of consuming content from the west, young people have the potential to create positive images of themselves and their neighborhood and upload these to social media, building new audiences and new visions. Often young people need to learn storyelling techniques, with basic skills imparted such as how to take better photos, or how edit simple videos. They need critical thinking skills enabling them to work productively with diversity, gender equality and to understand the meaning of ethics.

Conclusion

Through working with CACs with an understanding of the innate needs as humans for conviviality, belonging and creative expression, we needed to understand how to work smartly, to build with others using clear values around sustainability and social justice. By doing this we can jointly address the global and local challenges we face, build resilience, foster hope and intercultural harmony.

But the work of cultural workers will come to naught if government does not come to the table to do its job better, to deal with the significant deficiencies in the system, to address co-operative governance glitches, to ensure a properly resourced, consistently run, facilitative program that can make a difference to communities where they live. If Community Arts/Cultural Centres are truly the answer to the challenges faced at local levels, than it is indeed time for changes in national strategies and actions, and for the development of clear and implementable local cultural policies that are enabling.

Photo credit image on cover of the article: Tjapukai Aboriginal Park