Yogyakarta: A City on the Edge

A Special City

Yogja, as Yogjakarta, Indonesia, is fondly called, is a deeply cultural and educational city. Historically it was built in 1756, deliberately along Javanese cosmology and philosophical lines as a reflection of the universe - with the Merapi Volcano north, the Indian Ocean to the south and three rivers flanking the old city on each side, east and west. Its been intricately connected to Indonesia’s liberation struggle against Dutch colonists. Key to this history was the role of the Sultan of Yogja. As a result of this historical connection, the constitution, developed post independence, enshrined the Sultan as a governor of the "Special Region of Yogyakarta". Thus politically, as the city region, it is, unlike anywhere else in the country, the only place still run feudally within a democratic country. It is a city with many divisions and societal challenges, and one of the poorest in the country. It remains a cheap city to live in, which together with its cultural assets and friendliness, makes it a place that attracts artists and students. As we shall see it is a mixture of its various natural, historical, cultural and social elements that make it such an intriguing space, fomenting much of the dynamic artistic energy of the country, making it a place of cutting edge creative practise.

In this piece, you will discover a bit about Yogja, and you will get a broad view of its arts ecosystem and assets. You will understand some of its strengths and some of its resource challenges. You will get to understand a bit about the cultural funding and policy environment of Indonesia and how it relates to Yogja. Lastly we will start to glimpse what makes this such an interesting and edgy city for socially engaged practice.

Environmentally degraded but socially dynamic

Yogja, like many other Indonesian cities is an environmentally degraded city, with smog filled traffic, packed with scooters, cars and the odd bus. There are also numerous horse and carts and pedi cycles. Residents say that ten years ago it was a city filled with bicycles, but today, with cheap credit and the lack of a decent public transport system, cars and especially scooters are everywhere. The many ancient river ways are heavily polluted, empty plots of land are dumping sites, and villagers in nearby outlying farms regularly burn plastic in an effort to get rid of uncollected waste. The too narrow pavements are in a mess, small, broken and congested, with parked scooters, not an easy place for pedestrians. Not all of the public infrastructure is the result of neglect by people however, Yogja is in an earthquake zone and in 2006 suffered a massive quake causing over 5 700 deaths, and extensive injuries and damage to its built fabric.

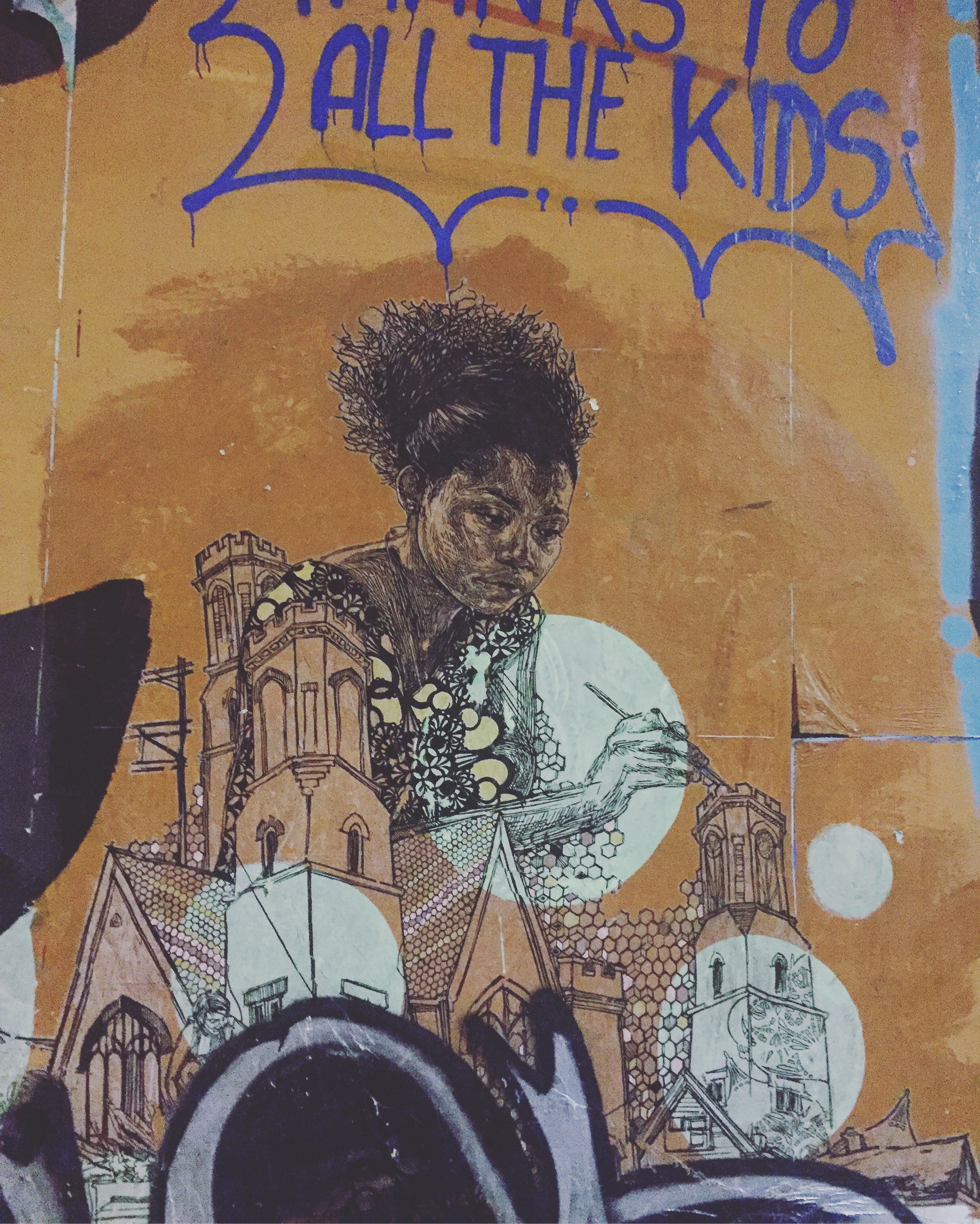

A pedicab passes an abandoned building damaged by the 2006 earthquake, adorned with street art

Despite the unfriendly public space, the streets are alive with people at all times - street food vendors, book sellers, people playing cards and chess, eating on the floor, cleaning ingredients for meals and sorting coal. In the tourist areas, the largely European and predominantly Dutch backpackers are sitting in bars and restaurants, eating local food and drinking beer, swopping stories of visits to Bali and the famous ancient Borabudur Buddhist and Prambanan Hindu temples, while Muslim Indonesians pack popular ice-cream parlors.

In the tightly packed kampungs, there is a mix of middle and working classes . People smile and greet each other and strangers as they walk past. The walls are filled with graffiti and beautiful street art. There is a smell of food being prepared and the air is filled 5 times a day with sounds of the adhaan (call to prayer) from the many mosques in the city. It feels safe, friendly, accepting and the community spirit is obvious.

A City of the Arts

Yogja is famous for a number of collectives working in socially engaged arts practises, edgy urbanists working on issues of sustainability and a vibrant music scene which includes proto-punks/hardcore, reggae as well as a great deal of traditional Gamelan music. It has a vibrant set of alternative spaces, regular art exhibitions, performance art and interventions. There are many exciting and cutting edge festivals taking place throughout the year and the arts scene is bouncing to say the least. In addition to the regular larger festivals (18 varied Yogja events belong to a British Council funded programme to build co-operation), there are numerous events taking place daily - from openings, to talks, to performances, education and music

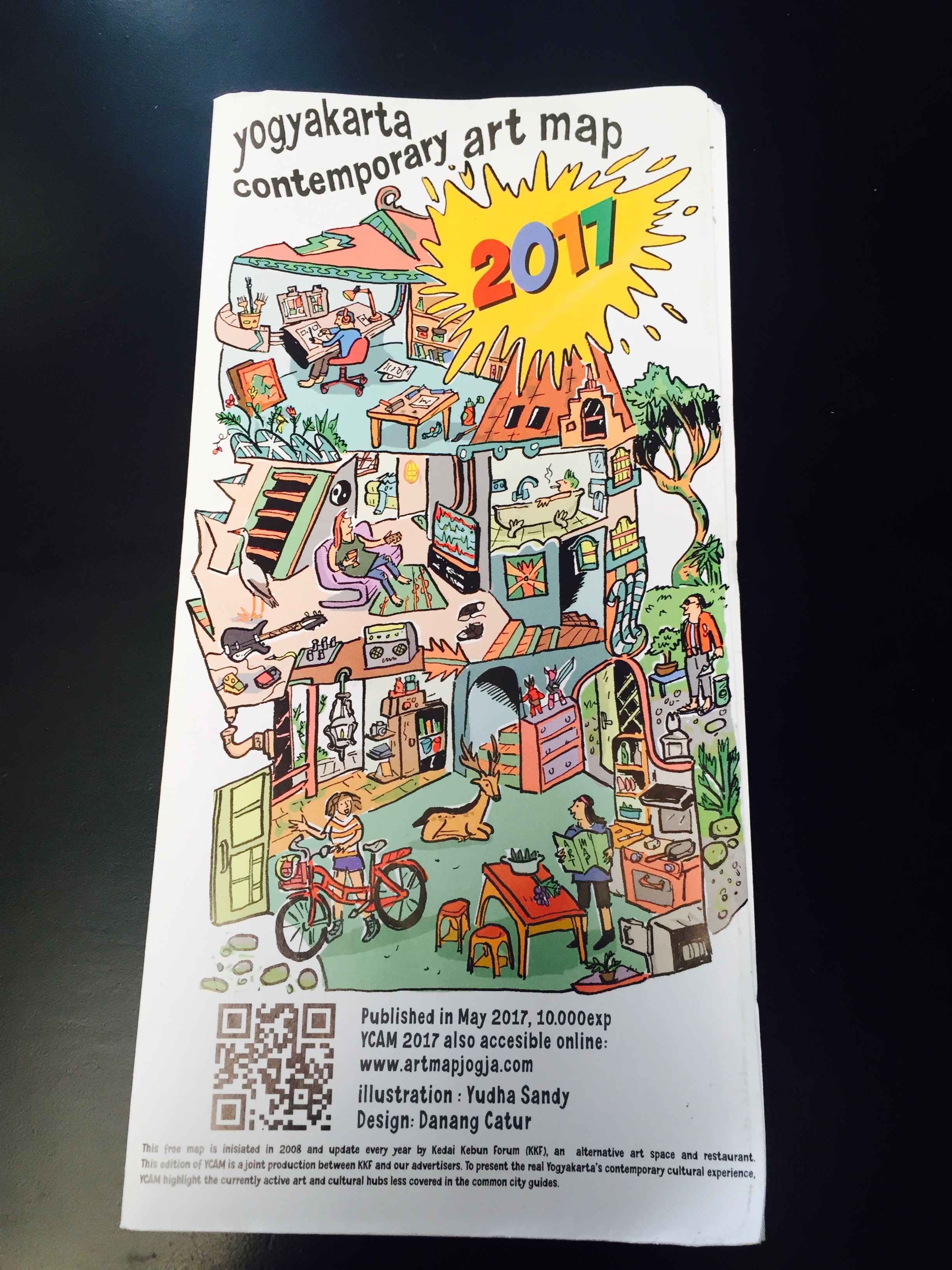

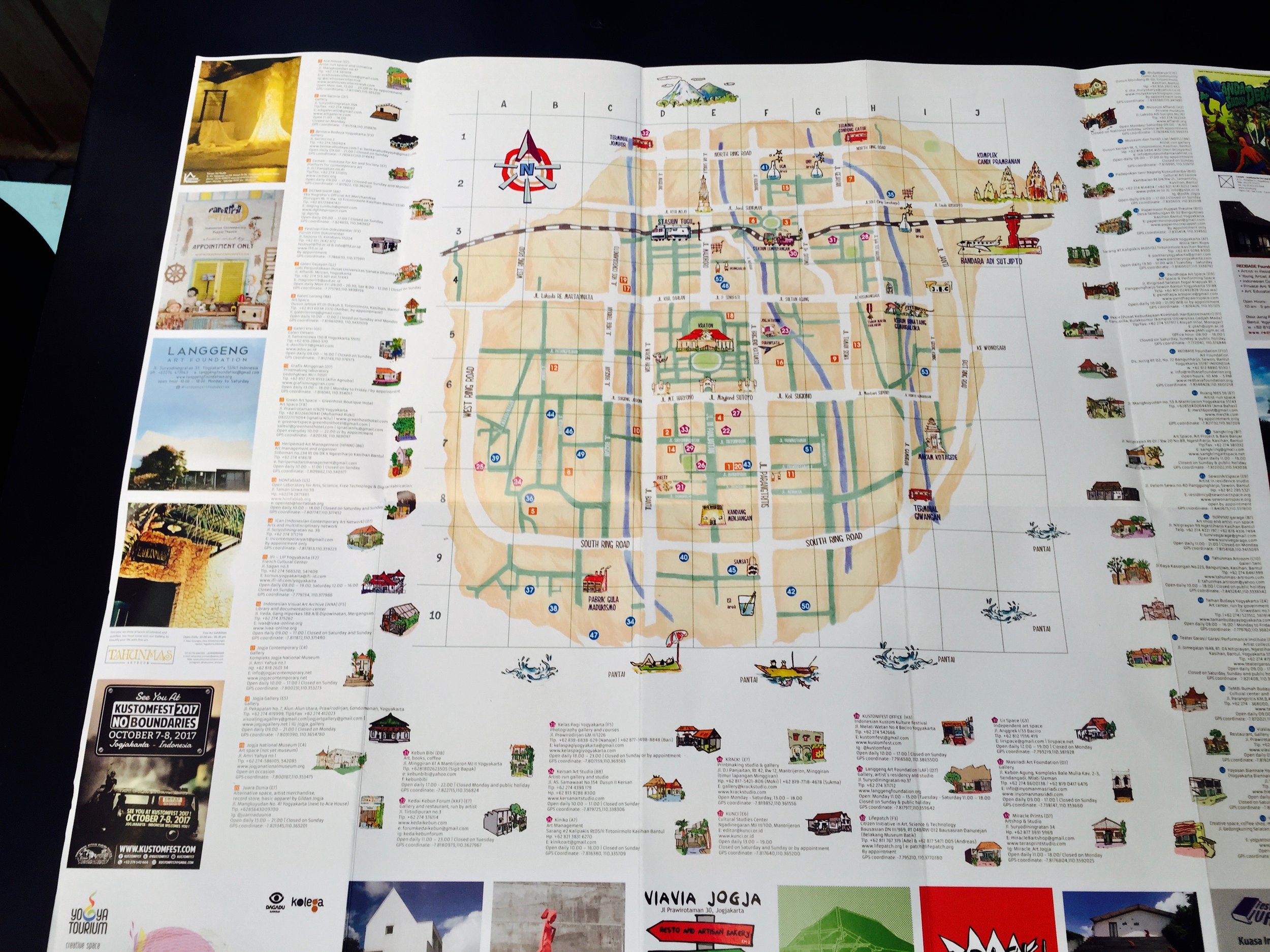

The art map of the city shows a surprisingly vast number of arts spaces, dotted, especially in the historic south of the city. The north is newer, wealthier, tends to be where the universities are, and is considered to be a more conservative area. Many of the arts spaces play dual or multiple roles, in addition to displaying or selling art. These may include having a café or restaurant, having a shop selling relevant products of some kind, having an attached arts residency or any other income generating aspect that fits with its concept. These help ensure economic sustainability in a fiscally tight city, but it also creates a network of spaces providing multiple services. The high number of residencies (often funded through artists visiting from wealthier countries) ensures an ongoing international crowd and a sharing of skills and ideas. Most of the arts spaces are acquainted with each other and there is a strong support system in place. One would imagine greater competition, but there is in fact high levels of co-operation. This does not however, interestingly, translate into any formal network structure for advocacy.

addressing resource challenges

There is not much money floating around for the arts, much of the recent foreign funding which entered the country post Reformasi has slowed down to a trickle. The Yogja regional government has recently received a large sum of money for culture from national government and some funding has been given to a range of organizations, including some of the long running spaces and events, as well as neighbourhood arts festivals. It is however in a difficult position of not being able to "spend" the money.

Government support for the arts in Indonesia is a massive challenge and the problem is both on the policy side and its administration. A national coalition, Koalisi Seni, set up in Jakarta to advocate around the most recent attempt of government to set up a cultural policy (a process which has taken more than 3 decades and is still not over), speak to the difficult task they have had of convincing government to be less controlling in its draft policy. Though they have been successful in influencing many aspects of the policy, especially around issues related to freedom of expression , there are still major challenges around grant making for example. Complex laws to prevent corruption have resulted in an overly administrative responses that makes the exercise of applying and claiming money complex and painful. Just as it is complex for artists to claim, it is equally difficult for government to organise around the disbursement of the funds. This has been one of the key challenges for Yogja's regional government.

It is often easier for government to "claim" initiatives as its own, but this comes with its own set of challenges in respect of artistic freedom. As a result most arts organisation will tell you that they prefer not to ask government for money and try to be as independent as possible.

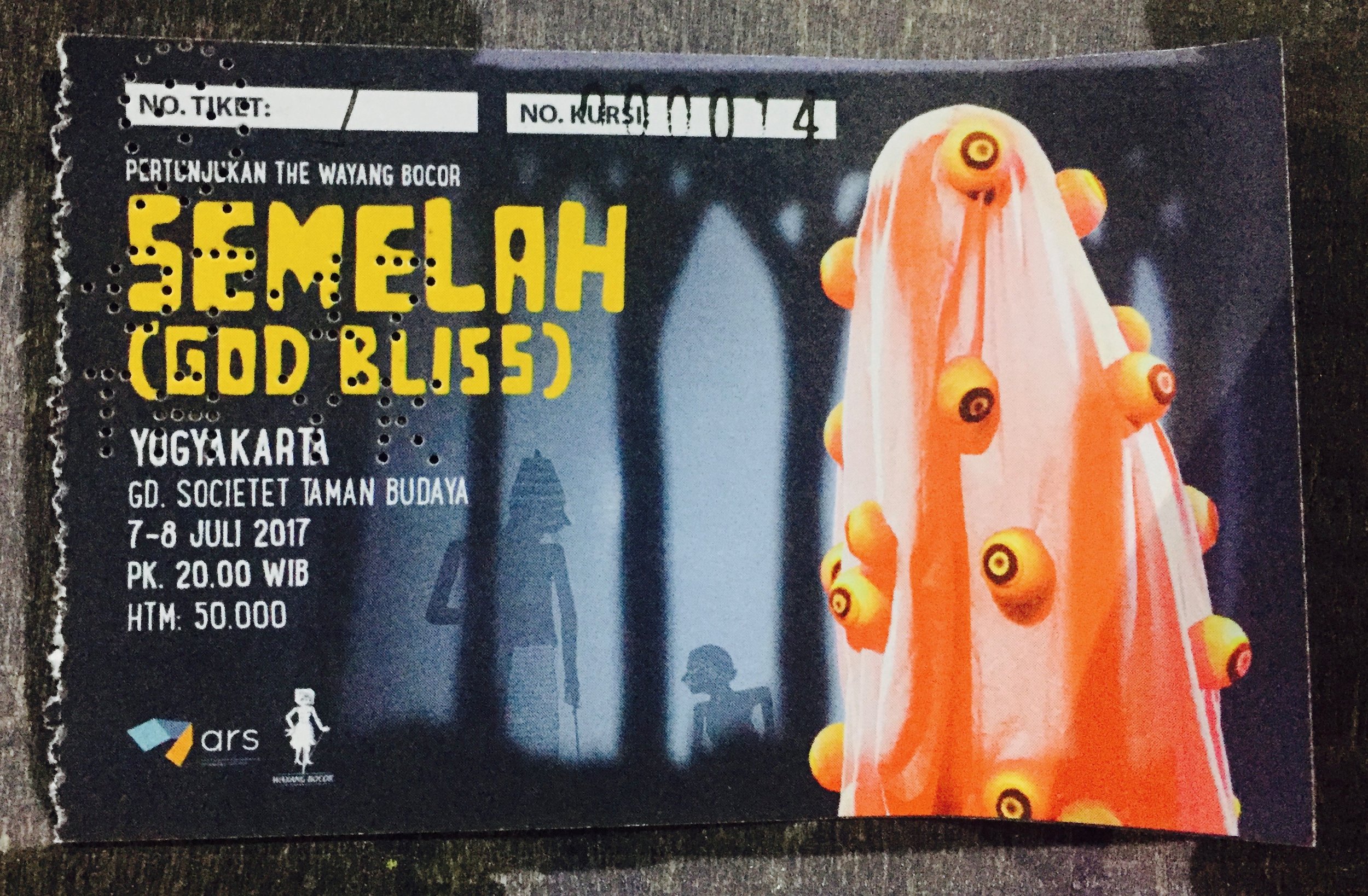

While the city rides on its high level cultural profile, government plays little significant facilitation role to develop the arts. One way it could be more supportive is via the provision of arts spaces and to some extent it does this. Taman Budaya (Garden of Culture) is such space, one of the few larger spaces for performances and contains studios. However it, like the Jogja National Museum (run by the Sultans son in law) are run inefficiently and are shabby decaying spaces, costly to hire. Arts bodies are nevertheless forced to use them for bigger events as there arefew large cultural spaces around.

Heritage buildings and history museums are also in a poor physical state, often with tired museum displays like those in Fort Vredeburg, the old Dutch Fort, now a museum of independence, which is nevertheless visited by tourists, families and students alike. In the age old story, common throughout the global south, the state has built or renovated such facilities, but has allocated little budget for operating costs and ongoing development.

In such a context of lack, it makes absolute sense that artists band together to provide support in collectives, loose networks and formal platforms. There is also support from some of the many academic institutions to draw on.

the role of the universities

Performance piece directed by Agung Kurniawan at PKKH

While artists feel there is not enough involvement by the city's many universities, in the cultural development projects of the city, there are various interesting projects taking place at a number of universities. One of these space is the Koesnadi Hardjasoemantri Cultural Center (or PKKH) at the University of Gadjah Mada. Part of a cultural studies department programme, it provides a large performance space as well as exhibition spaces for hire. In addition it runs its own programmes, which include a number of nationally focussed projects including a literary festival, and international projects such as a Gamelan Festival. It is not shy to court controversy, hosting projects on diversity and inviting various radical or marginal religiousgroupings to show their practises and engage in dialogue. By getting such groupings to meet each other, they hope to get people used to seeing each other in their differences, and to allay fears of the other by having them talk about themselves and show their artefacts and practises.

It also provides a safer space for artists to show controversial works - such as a performance piece dealing with aspects of the stories of 65/66. In this instance, the artist invited (now old) women persecuted as leftists to preform a script in which the audience were included as active participants, providing background sounds and snippets of radio broadcasts and songs.

Cutting Edge Practises

Eventually it is the presence of a great deal of cutting edge practise that makes Yogyakarta such an interesting place. The environment, which is slow and resonant, allows artists to engage with each other, with their histories, and with new ideas and forms coming through residencies and events. It creates a space of quiet and humble reflection that may be hard to imagine in a more frenetic city like Jakarata, or a wealthier city like Bandung.

The highly regarded Indonesian Institute for the Arts, Yogyakarta has fostered a number of students, who may challenge its curriculum, but are now artists who have produced some astounding projects. These push boundaries to their furthest edges, productively disrupting the comfort zones that local society could easily slip into.

In the next article you will meet some of the many collectives and organizations active in the city and hear about their practises