The Cultural District in Newtown, Johannesburg

A public sculpture of the famed and tragic superstar so loved by South Africans: Brenda Fassie or Ma Brrr, in front of the old Baseline Music venue.

The Newtown Cultural precinct, or "The Market", as it was called in its earlier days, is a 41 year old cultural district on the western edge of the Johannesburg inner city. Its been a personal source of interest since my late teens, as I began to explore what culture and creative expression meant in Apartheid South Africa. This fascination with the district's story continued through my professional life, where I have been involved in the management aspects of culture: art, heritage, design and diversity and its relationship to cities and to societal transformation. Newtown remains a source of enduring interest and I am currently working on my postgraduate studies, in the field of human geography examining it as my case study, looking at urban cultural policy and cultural clusters. In this piece, I will give you a very broad overview of the project and what makes it such an interesting story for me.

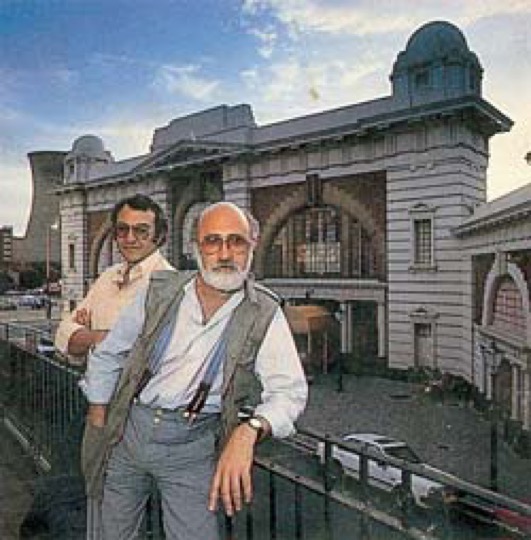

Mannie Manim and Barney Simon, founders of the Market Theatre. Photo by Gisele Wulfsohn

An organic cultural cluster

The organically developed cultural cluster which emerged in Newtown, Johannesburg, known unofficially as "The Market", was a unique, regionally relevant, racially diverse and vibrantly charged arts led space, at the height of apartheid repression. In its time it had significant local and national cultural influence through a range of initiatives that emerged from slow brewed cultural field, held together by supportive public space. The area first took on a cultural edge in June 1976 with the establishment of the Market Theatre, which would develop an internationally and nationally acclaimed reputation as a place showing quality productions pushing aesthetic boundaries, was politically radical, and open to mixed race audiences. In fact it was one of the few places in the country where people could legally mix across the apartheid color bar and was therefore a unique space in itself.

Timbira with Christo Leach in Newtown in front of Kippies Jazz Club. Photo by Ronnie Levitan from ADA Magazine 10: Johannesburg Special. '92

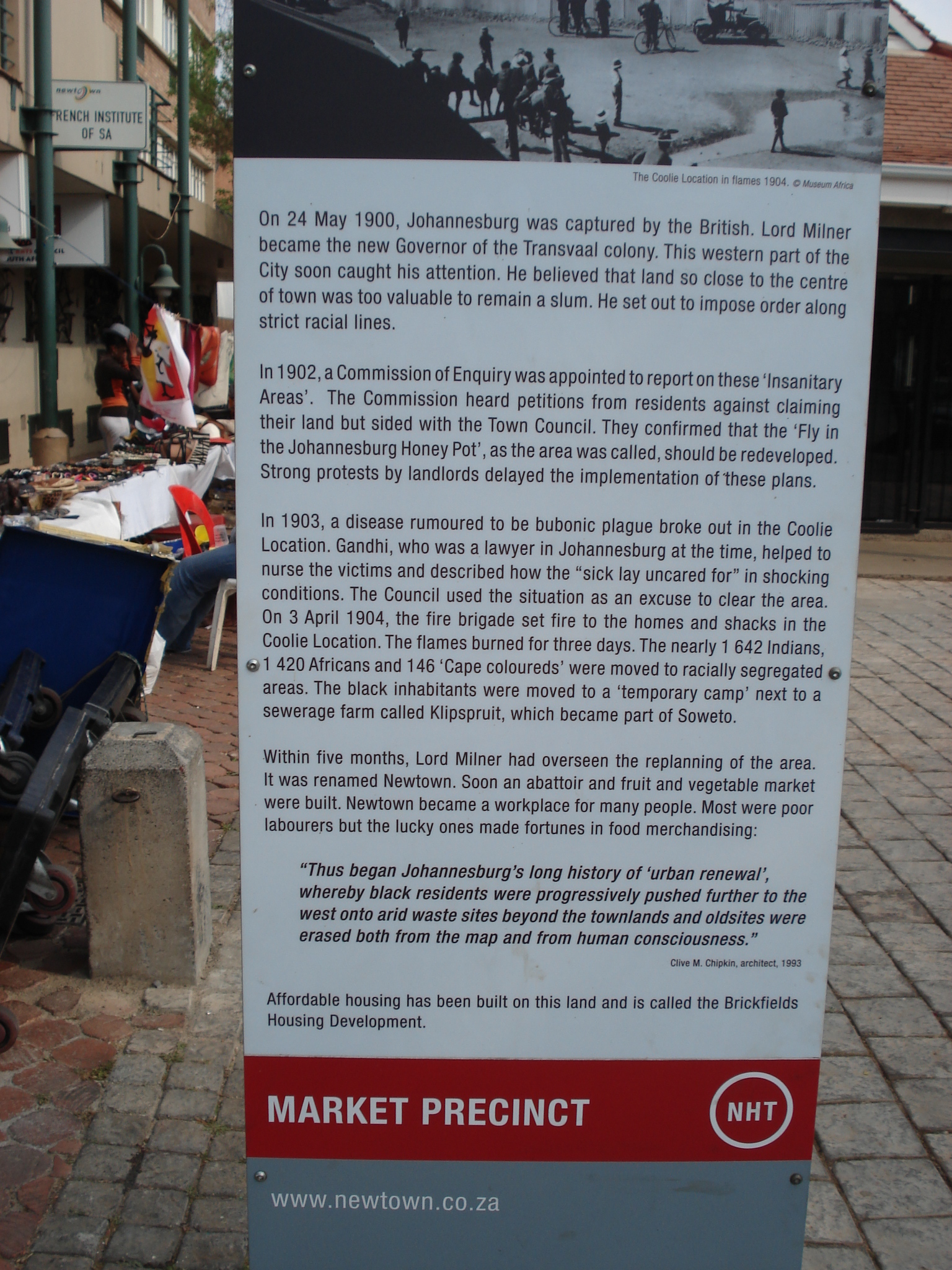

The reason it was a "grey area" in a highly segregated country, had to do interestingly with a zoning law. The site the Market Theatre was established in, a section of a majestic Victorian building, was in fact a defunct municipal fruit and vegetable market. It had been zoned for business and was not segregated. As a result of this quirk of history "The Market" attracted a variety of diverse people who attended not only the "struggle theatre" for which the Market Theatre had become famous, but who frequented the other cultural institutions and creative industry businesses, bars, restaurants, shops that had agglomerated around the theatre. The part of Newtown the "Market" was based in was Johannesburg's first industrial district established formally in 1904. Because of the municipal market, which was later moved to Crown Mines, the area became home to the city's agro-food processing industry. It was in addition, the site of a the city's first power station and a public transport servicing hub - both of which had stopped operating by the late 60s. As the industrial area slowly died, with businesses initially attracted to the fruit and veg market moving elsewhere, the cultural sector began to take over many of its now deserted buildings.

By the late 80s, and at its height, The "Market" included the Market Theatre Foundation (with its 3 theatre spaces, gallery, Photo Workshop and Theatre Lab), the FUBA Arts Centre, The Artists Proof Studios, The Newtown Gallery, the Mega Music Warehouse, Shifty Records and the Kippies Jazz Club, amongst others. In addition there were shops, restaurants and bars, including the infamous Yard of Ale and Gramadoelas. The Saturday Flea Market, run by avant garde artist Wolf Weineck, became a major attraction, the first of its kind in the city which turned the 'cultural district" into a major hangout spot. The inclusion in the area of a music platform on Saturdays was a huge hit. By then the cultural district itself was relatively small and intimate. It included the theatre across which was a block where most other organisations were based, with a small public space in between. This was a pedestrianised street, with Kippies on one end. Here is where most of the action happened, except on Saturdays when the flea market took place on the large Mary Fitzgerald square. Newtown was in those days one of the most significant, culturally relevant spaces in Johannesburg if not in South Africa and attracted a large number of important cultural workers, artists, journalists, activists, the international diplomatic community and others.

To get lunch at the Yard of Ale you had to book in advance – you had to pay a cover charge to get in. It was packed! Similarly Harridans – it was very thrilling and some time later the thing shifted a little bit, but still the charm remained. I remember one particular Friday lunch time stepping out of the gallery and Barney Simon and Athol Fugard were sitting on the bricks under a tree intensely talking to each other; Hugh Masekela was walking out of Kippies with a couple of birds on his arm; in the Yard of Ale Max Du Preez and Jacques Pauw were sitting and talking to Dirk Coetzee – in Harridans having lunch was Joe Slovo. And I thought fuck it, in short, this works for me. I like it! [Laughs]

[interview in 2007 with Ricky Burnett about the early 90s– curator and owner of the defunct Newtown Gallery]

It had never been planned, was never branded or officially named and had no management structure- "The Market" was therefore a completely organic initiative.

A state driven cultural district

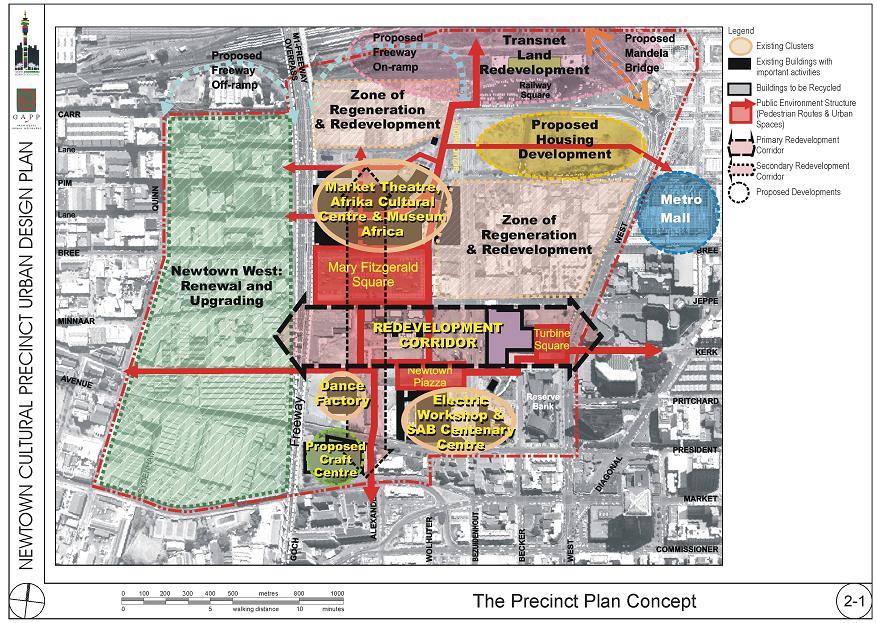

From 1990 the City established the country's first municipal arts and culture department and employed Christopher Till, who had previously been director of the national Gallery of Zimbabwe and the Johannesburg Art Gallery to lead it. Under Till, the City assumed control of the site and renamed it the Newtown Cultural Precinct, inspired by examples at the time from the UK where industrial districts were being used to regenerate and reposition cities. The site was extended into the old power station site, and one of its grand spaces, the Electric Workshop was turned into a major events space. Museum Africa was opened as a centre piece. Till "squatted" the city owned sites with a number of cultural organisations, many of them formed as anti-apartheid bodies, and who were given spaces at pepper corn rentals. He also initiated two major events to activate the space - the Johannesburg Biennale and Arts Alive. The two iterations of the former would significantly alter the South African landscape and bring international acclaim, local admiration and considerable critique. Till had a savvy understanding of working dynamically with culture and with the opportunities in his environment, and made a success of laying a foundation for cultural program of excellence built on a strong Africanist approach with an eye to the global. However his perceived "over-individualistic" style, the failure of the second biennale to achieve significant numbers and shifts that occurred within the city during political transformation led to his resignation by 1998.

Bollards in Newtown

From 1999/2000 a new municipal entity, the Johannesburg Development Agency (JDA), took over the site in a partnership, at the time, with Blue IQ (provincial government's investment arm) and panoptically planned and drove various consumption centered, built environment heavy, place promotion initiatives. Although there were moments when the project was culturally vital, over time the project has been increasingly sapped of its creative energy. Many organisations left or were forced out and its supportive form was shattered. After significant cuts in funding from 2005, the project limped on further into the present day, with a short reprieve during the 2010 Soccer World Cup, when it received a spruce up as the city's main fan park. As a site it now has a number of housing initiatives, a non-descript mall, two major property developments accommodating corporate business headquarters, a heavily designed public space and improved transport access. The Market Theatre, once an independent, anti apartheid non-profit is now a government institution which recently moved its Theatre Lab, Photo Workshop and administrative functions into a spruced up new development, Market Square.

There are few however, who would see the project in Newtown objectively as a successful cultural development project today, and in many ways its trajectory is a reflection of the broader story of the changes in South Africa and Johannesburg, politically, economically and in terms of urban and cultural policies.

Ten years ago you didn’t need a plan to go to Newtown. You’d simply take a walk around knowing that in no time at all you’d hear the “1-2-1-2” of a mic check or live music blaring from Bassline. You could bump into poets heading to Shivava for an open mic. And if you were in the mood for a good laugh. Or awkward silence as a comedian bombed out on stage, you’d check out the dungeon at Horror Café. And if all else failed, you’d go hang in the park for the inevitable cypher or jam session. As I write this, it breaks my heart that all these venues are no more, except for Bassline. But even this legendary space is closing its doors at the end of this month….Where is the arts in this so-called “Arts Precinct”?

Qhakaza Mthembu 15/12/16: in 'Dear Joburg, where is the “arts” in the Newtown Arts Precinct?'

Why the cultural district in newtown is interesting as a case

Although the district has been around for some time and has attracted a bit of research interest, including a excellent MA thesis by an ex employee, the site offers a great deal of potential for further exploration because of its wealth of stories. Interestingly despite the more than R344 million invested in the site since 2000, it has never been formally and objectively evaluated, with the JDA generally, and predictably, pitching it as a successful culture led urban regeneration project. Thus my interests in it are several:

A unique cultural IMPACT

Firstly, it was a unique project culturally in its time, with an important impact on arts and South African society. A number of cultural workers like myself were significantly influenced by it professionally and personally. The unique intercultural nature of the site and some of the important projects that were spawned out of it - the Voelvry movement and the Johannesburg Biennale are just two initiatives of national importance, which re-shaped the cultural landscape of South African. It also had an impact on a younger black creative community in Johannesburg in the 2000s, a moment that happened despite, rather than because of formal dynamics of the Newtown Cultural Precinct project. Perhaps its enduring legacy was its non racial nature pre '94. which could have taught us much about how to work with nebulous terms like "Social Cohesion" which looms large in South Africa's cultural policy, but finds few or any practical or realizable manifestations around the country. We are still a highly racialised and increasingly intolerant country.

Mary Fitzgerald Square

An example of a cultural district/cluster.

Second, as a cultural district model generally, it has interest. Spatio-cultural initiatives (clusters/ districts/ flagships/ etc), formal and organic have been around for a while, but more so in the last three decades. They have became a stable of urban policy making for many cities wanting to capitalise on the opportunities culture may bring, inspired by the likes of consultant/theorists Richard Florida and Charles Landry. Some of these strategies are around positioning a city globally - a way to raise its brand profile as it were. Others are economic development strategies, often industrially oriented. A large number have been built environment focused: constructing arts and culture spaces, public space upgrades and the like. The Bilboa effect, as its called, is one form - a flagship driven initiative, But there are numerous other examples around the globe, some anchored by "starchitect" designed buildings, others more modestly made. There is also a number of more community based spatio-cultural projects or initiatives driven by networks. It has taken a while, but there is now a growing body of critical academic literature looking at these projects beyond the celebratory. There is more interest in the dynamics of the making of cultural spaces at various scales, much of it increasingly "techy" - in very positive ways. These studies are not just concerned with the narrow built environment/economic considerations, but are increasingly concerned with the participatory place making, sustainability and social justice considerations of such projects. They place emphasis on evidence based planning and explore more critical approaches to setting objectives, evaluating projects and developing the organisational forms.

The Urban Design Plan for the area circa 2002

As a municipal project in Johannesburg

As a particular South African cultural district project Newtown has interest because of its failures. The case provide us with rich opportunities to learn how to improve urban cultural policy making and its implementation in space. In most cases, in working with projects of this nature - organic or state driven, policy makers have had to learn the importance of working with the dynamics and importance of a city or neighborhood's cultural assets. Such assets may include arts bodies, creative industries, heritage and other non-profit organisations, but there are also intangible considerations, such as local wisdoms, values and networks which may extend beyond the boundaries of the site.

What's been interesting in this case is that since 1990, the Newtown project shifted suddenly from a bottom-up to a top down planning and management framework. Local arts and culture bodies increasingly lost agency in the process. From 1999/2000 it shifted again from being a cultural development project to a city positioning and urban renewal/property development one. This more instrumentalist approach further alienated the cultural sector, and was exacerbated by the nature of the organizational model employed, which made real participation/co-production virtually impossible.

Another critical feature of the project was the international consultants influence in planning the site on an overtly consumption driven model. Many of the nuances of Newtown and its links to its anti-apartheid history were treated, by the JDA, as heritage material for branding, or as a background story, rather than as part of its living dynamics. Its regional importance, especially its links to a black cultural development sector for whom the site was historically a key connection in the early days did not get sufficiently deep recognition.

What's up with the Newtown cultural precinct now?

In the last few years, the Joburg Property Company, the municipal entity who owns most of the property in the area has been considering a way forward for what is effectively a stalled project. Another report was recently prepared, again outside of any impartial evaluation of the sites long history, and in an urban cultural policy vacuum. The City's Arts, Culture and Heritage department is not an active partner in any of these plans, despite its earlier role and its control of the seriously compromised Museum Africa in the centre of the site. Its sad to see the sidelined department functioning on around 50% of its capacity, with a budget that has not increased much in recent years.

Ultimately the project raises questions for me about the city's understandings of culture and to consider its potential for transforming cities and for participatory governance. Research on Newtown as a cultural space, allows me to think about urban cultural policy, cultural planning and other spatio-cultural projects (clusters, districts, flagship initiatives, culture as a tool for urban regeneration) in South Africa in particular in new generative ways. My interest is to understand the potential of cultural clusters beyond the economic, to understand their potential in advancing a more just city.

Its important, I believe, to share writing on Newtown, so over the course of the coming year, I will be posting occasional pieces on the initiative. Some are relevant to my study, while others seek to document an important story that has not been told in a more public ways previously.